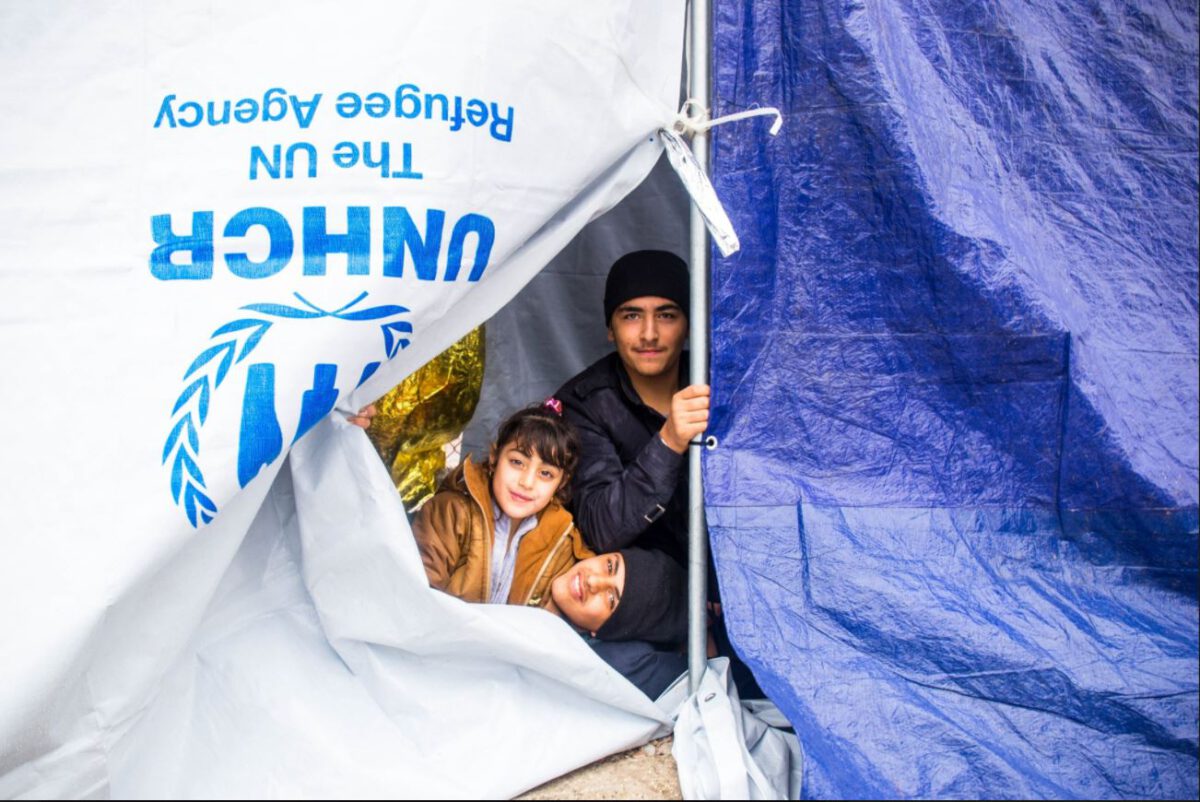

This is the current situation on Lesvos

I travelled to Lesvos in July to see what the current situation is in the new Mavrovouni camp after the fire in Moria. I also met with the Frontex field force to discuss the current situation and the pushbacks by the Greek Coast Guard. And I visited various NGOs and civil society actors who are fighting to change the situation politically, but also make offers so that refugees have the possibility to get through their difficult everyday life a little better.

In the On the night of September 8-9, the Moria camp burned down completely. At the time, 12,600 people were living there in cramped quarters in undignified conditions. The camp is a symbol of the failure of European refugee policy, which fails to guarantee people fair asylum procedures and respect their human dignity. Nine months after the fire in the Moria refugee camp, six young Afghans are sentenced to long prison terms for arson. And this despite the fact that none of the witnesses present saw them on the alleged night of the crime. The trial and the verdict have come under criticism.

The new Moria

The new Mavrovouni camp was built on the site of a former military training area. Around 4350 people currently live here in containers and tents, without running water or electricity. They can only leave the camp, which is bordered by barbed wire and walls, to a limited extent.

With Tareq Alaows I visited the new camp at the end of July. The last time Tareq was on Lesbos was in 2015. As a Syrian refugee, he slept on the street and tried to get on from here. Today he lives in Germany and is active in the Seebrücke and the Green Party.

Manos Logothetis showed us around the camp; he is the Secretary General of the Ministry of Migration and therefore responsible for the camps in Greece. Also present were the local representative of the European Commission and the director of the camp, who was also responsible for the former Moria. In response to questions about the lead contamination of soilthe access of NGOs to the camp and the massive Restriction of freedom of movement they answered evasively. Greece, unlike Germany, has no problem with walls, Logothetis said when asked why a refugee camp is walled off. In his opinion, one must also protect the local population from the refugees.

Conditions in Mavrovouni

The summers on Lesbos are very hot and the temperatures sometimes rise to 40°C. In Mavrovouni there is hardly any shade. The tents are in the full sun and it is dry as dust. The dust settles on everything and is everywhere. In the camp I visited a family in a tent to talk to them about the situation. It was even hotter inside than outside. I found it almost unbearable after just a few minutes. The people there have to spend their lives in such tents, where it is too hot in summer and where they freeze in winter. With the location right on the coast, the tents also don't protect enough from wind and water. Medical care is poor. Shortly before we visited the camp, a three-month-old infant died. According to local news, the child was reportedly vomiting the night before he died, but was not taken to a doctor in time.

Large construction site

The camp is currently a large construction site as water and power lines are being laid and housing containers are to be erected. The commission and the Greek government have promised that no one will freeze in tents this winter. I really hope that they will keep this promise. Every year since 2015, people on the island have had to freeze in tents during the winter.

Although Mavrovouni was only intended as a temporary emergency solution after the fire in Moria and there are already plans for the construction of a new camp, the camp is being expanded. The reason for this is that the construction of the new camp will still take some time and the people cannot continue to live without running water and electricity until then. In addition, the current camp will remain in place and serve as another emergency solution in case more people arrive on the island again. It is unclear whether the new camp will actually be built and whether refugees will ever be housed there. On Lesvos, there is a dispute between two municipalities on the issue and only a very narrow majority in favour of building a new camp. In September, the Commission was still promising that Mavrovouni would be a temporary camp. I therefore find it strange that construction is now taking place everywhere there and that it will probably continue to operate for a long time to come.

Lack of perspective

A large part of the people in the camp come from Afghanistan – the most unpeaceful country in the world according to Global Peace Index. With the current Taliban advance, situation on the ground worsens every day. Nevertheless, many residents have received a second rejection of their asylum application and remain in the camp in fear of deportation and without prospects and support. The applications are no longer examined to see whether the people were safe in Afghanistan or Syria, but only whether they were safe in Turkey. This also shrinks their legal prospects. The atmosphere in the camp is extremely tense and the situation has a strong impact on the mental health of the refugees.

Many people also suffer from physical impairments, some sit in wheelchairs. They can move around the camp only poorly and receive hardly any support. And with some things you also wonder how this could happen. For example, there is a toilet for people with disabilities at the top of the camp, which is hardly accessible with a wheelchair.

Years without education

Around 40% of the people in the camp are children. Many of them have never attended school. In my conversation with the head of the UNHCR on Lesvos, Astrid Castelein, it became clear that this will not change any time soon. Although attempts are being made to organise informal education for the children, even that is not guaranteed. The goal should be to create formal education and reliable structures for the children.

In addition, the UNHCR expressed concerns about the limited access to the camp, the accommodation of people in tents in winter and the pushbacks. Neither the UNHCR, nor NGOs or journalists can approach arriving people when the Greek coast guard is on site.

The situation on Lesbos is frightening. Not because there are too many people in the camp on the island, but because hardly anyone can make the crossing. At present hardly any rubber dinghies reach the island. This is a consequence of the pushbacks by the Greek coast guard. The vast majority of those seeking protection are intercepted and mistreated by the Greek coast guard. They are not allowed to apply for asylum, their boat engines are destroyed, masked men drag them into Turkish waters and leave them there. This is highly criminal, but the inhumane treatment of people in need is now so commonplace that it doesn't even stand out. A 17 year old told me he fled the war in Syria and the first thing he had to do in Europe was run. The police chased him with dogs, wanted to dump him at sea too, but he managed to hide.

These crimes have been proven a hundred times over, and the EU Commission and the German government have prevented them from having any consequences a hundred times over. At the EU's external borders one can see in fast motion how democratic principles are dissolving and arbitrariness reigns. Those who are not white all too often have no rights at the European external borders. Those who are not white are defenceless against state violence.

Visit to Frontex forces on the ground

The Frontex forces on the ground also know about the pushbacks, but they systematically look the other way so that they can continue. Frontex's aerial reconnaissance on the ground has been discontinued because it would document too many of the obvious pushbacks and human rights violations and Frontex would then also have to complain about them.

Many people are forced out of Greek waters in the Aegean. The engines of the boats are dismantled and the people are left adrift in the Aegean, unable to manoeuvre. The role of Frontex in these pushbacks, which are contrary to international law, we have just recently discussed in the Frontex Inquiry Group of the European Parliament investigated. The people who can still reach the island are housed in a quarantine camp far away in the north.

I have exchanged views with Frontex on the restructuring of the agency and the work of the employees on the ground. Frontex's self-declared role is to assist Member States with border management. While Frontex denies involvement in pushbacks, the fact that they are taking place is hard for Frontex to deny as well. Even if they are not officially allowed to say so, it becomes clear in informal conversations that at least some Frontex officials are of course aware that pushbacks are taking place. The Greek police describe the cooperation with the agency as excellent, but they do not want to reveal details about the working procedures. When I visited a ship of the Italian Financial Guard, which Italy sent to Frontex, I could see for myself how well equipped these ships are. The ship can reach speeds of up to 120 km/h. Despite this, Frontex is conspicuous by its absence in sea emergencies in the Aegean. Many of the Frontex officers only stay on site for a few months and therefore hardly have the opportunity to familiarise themselves properly.

Police arbitrariness and restricted freedom of the press

There are numerous reports of police violence on the island. Thus, people seeking protection tried to reach the island on a rubber dinghy. At the maritime border between Greece and Turkey, the respective coast guards created waves, which is a common practice. This is just one example of the lack of rule of law in the country. I too witness this time and again, for example when Greek police officers threaten to lock me up because I want to record an interview outside the camp. The freedom of the press is massively restricted. Many members of the press are not allowed access to the new camp.

My visit to non-governmental organisations

But there are also many projects and organizations on the island that do not accept this situation and want to continuously improve the situation on the island. One example is the Community Center of One Happy Familynot far from the new camp. There are sports activities, a cybercafé, a library, a workshop, a safe space for women* and girls, psychosocial counselling, a garden, a café, a playroom for children and more. The center is managed by refugees and international volunteers. It is located within walking distance from the camp and offers many recreational and educational opportunities. It is also much more comfortable than the camps. One problem, however, is that many of the camp's residents are not able to use the facilities, or only to a limited extent. This is because they are not always allowed to go out when they want to or because they have to queue for a long time in the camp for everything, especially food, and thus lose time. When they are allowed to leave the camp, many use the time and their little money to buy more food and things that are needed in everyday life.

There is also a permaculture farm, numerous department stores, legal advice in the Legal Center Lesvos and much more. In the school of Wave of Hope painting courses are held and the pictures of the refugees are exhibited. On Lesvos the concentration of NGOs is quite high, on other islands like Chios and Samos the situation is different.

The misery is politically intended

The situation on the ground is absurd: for example, there are numerous water and soap dispensers in a donation-filled warehouse next to Mavrovouni, just waiting to be connected and set up in the camp. But the camp management prohibits the dispensers from being transferred to the camp.

There is a lot of solidarity with the refugees at Europe's external borders. This is shown by the many donations, the NGOs and also the many cities and municipalities that show solidarity and voluntarily agree to take in more refugees from the external borders. But they are not allowed to.

The people on Lesbos would not have to live on dust-dry ground without water and electricity, isolated in tents without medical care. On the contrary, there is a political will for people to live in misery. This undignified situation at our external borders is created to deter. The situation on the ground is deliberately kept so bad that others do not apply for asylum in the EU because they are afraid that they will end up in these camps. It is a disgrace that we treat people who need our help in this way at our external borders. Yet we should actually be proud of helping people and taking in refugees.