Migration pact – Why the EU Commission's proposal does not prevent another Moria

The EU Commission's proposal for the migration pact won't prevent another Moria. On the contrary, it would cast the model of the Greek mass camps in legal form. Border procedures and closed camps at the external borders would become the norm in Europe. The failure of the Dublin system would be perpetuated and escalated, further without a mandatory solidary reception of refugees. Germany is also threatened with considerable tightening of asylum law. The Commission's proposal on asylum procedures tightens up the 2016 Asylum Package II and casts it in European law.

European values are being damaged

With the Pact, the EU Commission has set itself the ultimate goal of European unification at any price. In order to achieve this, it accepts that refugee protection and our common European values will be severely damaged. Instead of orderly and fair procedures throughout Europe, the Pact will exacerbate the crisis at the external borders. The Pact must now be discussed and agreed in the European Parliament and among Member States in the Council. We Greens will campaign in the negotiations to end the systematic suffering of those seeking protection at the EU's external borders. A fair and humanitarian European asylum system must emerge from the ashes of Moria.

At this link you will find our proposal for a fair asylum system in Europe.

Border procedures: mass detention of refugees

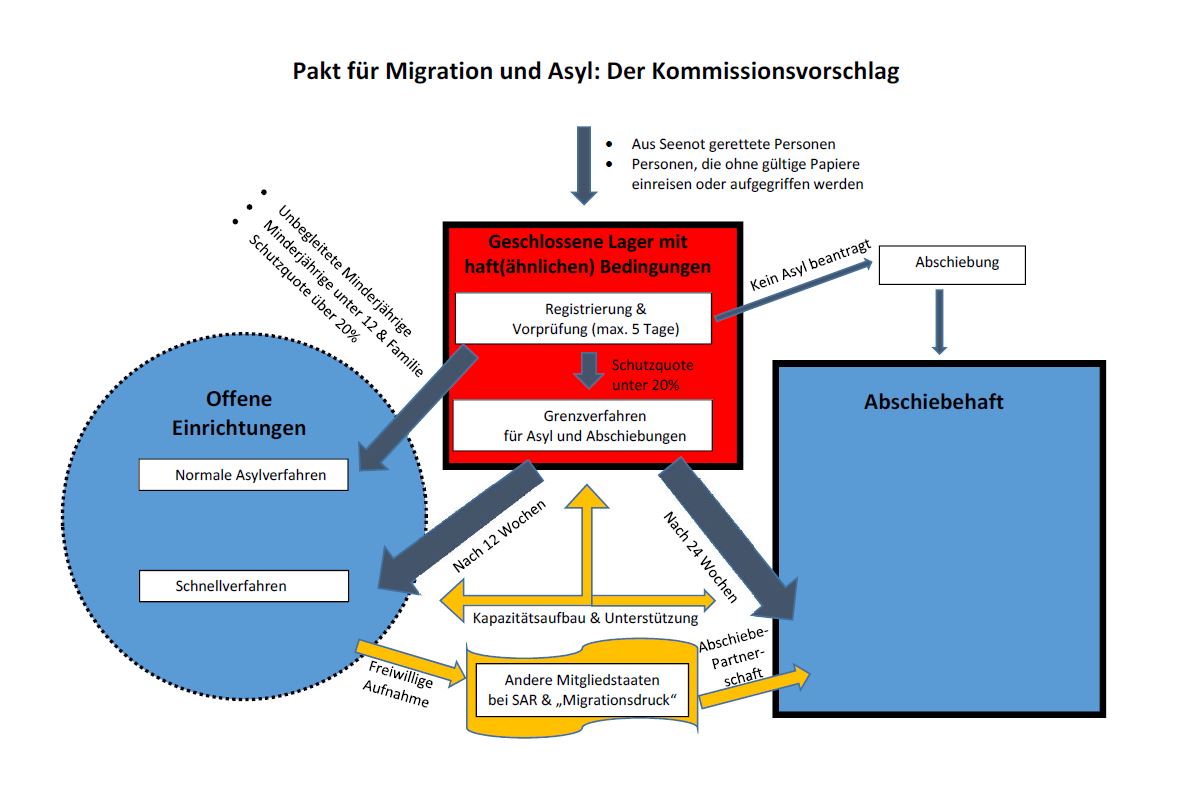

According to the EU Commission's proposal, all persons who want to enter the EU without valid papers or are apprehended should be taken to closed camps under detention conditions. This also applies to those rescued from distress at sea. Those arriving must first undergo a preliminary examination, which must be completed within five days. This includes registration as well as a health check and a security check in European border and security databases.

The pre-screening should also record what type of procedures the arrivals

and whether they will continue to be held under detention conditions:

– A normal asylum procedure should only be given to those who come from a country with a recognition rate of more than 20 per cent, i.e. when at least everyr fifth asylum seeker from this country in the EU as a refugeer is recognised.

– A fast-track asylum procedure under detention conditions at the border (border procedure) must be undergone by anyone who comes from a country with a recognition rate of less than 20 per cent, anyone who poses a security risk or anyone who provides false information about their identity.

People from a previously safe country of origin (e.g. the Balkans) or from a safe third country (e.g. Syrians arriving via Turkey) must also go through a fast-track asylum procedure, but not necessarily at the border.

– Those who do not apply for asylum should be deported directly from the camp.

The Commission is thus significantly expanding the detention of refugees. According to the Commission's plans, most fast-track procedures are to be carried out in closed camps at the border. Only unaccompanied minor refugees and children under 12 and their families are exempt from this. They will be housed in an open facility during their fast-track asylum procedure, just like asylum seekers going through a normal asylum procedure. under this procedure, more than half of irregular arrivals would have had to go through a border procedure under detention conditions in 2017 and 2018 because they came from countries with a recognition rate defined as low. In 2019, by contrast, more people in need of protection arrived from countries with higher recognition rates.

Detention of asylum seekers to be extended

With its proposal, the Commission wants to send a signal of deterrence. In order to do so, it accepts that the protection of refugees and their human dignity will be undermined. It wants to drastically triple the detention period from the current 4 weeks for border procedures to 12 weeks in the future. Only if the asylum procedure cannot be completed in this time will the asylum seekers be placed in normal refugee accommodation.

Those who are rejected are also to be deported directly from the border camps without being allowed to set foot on European soil. If this is not possible by 12 weeks after the end of the asylum procedure, they are to be transferred to detention centres for deportation. The crucial question, namely how the dovetailing of asylum and deportation procedures is to lead to an increase in the deportation rate, remains unanswered, as does the question of how the Commission intends to ensure that the Member States carry out asylum procedures more efficiently than before. The Commission is creating new camps with the border procedures. But it has no answer as to how a second Moria is to be prevented.

Dublin and refugee distribution: overcrowded camps remain

The EU Commission had declared the Dublin system dead - and yet wants to retain it as a core element of the European asylum system with the pact. What changes with the pact is above all the title. Dublin is now called "Migration Management". The Dublin system is a system of shifting responsibility to member states at the EU's southern external borders. The member state in which ae refugeesUnder the Dublin system, the first person to set foot on European soil is responsible for asylum procedures and accommodation. Instead of finally replacing the system of shifting responsibility with a system of fair sharing of responsibility for those seeking protection in Europe, the Commission wants to cement it with the pact.

In future, member states will have to wait much longer than the current 18 months for ane Asylum seekersn be responsible. The right of other member states to send back refugees who have irregularly moved on to another member state only expires three years after they have been recognised as refugees. The Commission also wants to make it easier for member states to send back asylum seekers who have moved on. Asylum seekers themselves should not receive any support and accommodation if they move on irregularly. One of the few positive aspects in the Commission proposal is the extension of family reunification to

Siblings.

Deportation sponsorships instead of solutions – Southern EU countries continue to be left in the lurch

The Commission's proposal increases the responsibility of southern EU countries such as Greece, Malta, Italy or Spain - without offering them sufficient solidarity. The system of flexible solidarity proposed by the Commission is complex. It amounts to giving member states a whole range of fallback options to avoid having to take in refugees. Solidarity will be obligatory in case of "high migratory pressure", but not the reception of refugees. Member states can, under the Commission's proposal, instead:

– Provide capacity building – such as through the provision of fingerprint scanners for the registration of arrivals.

– provide operational support to these countries – for example by deploying border guardsor asylum expertinside

– by cooperating with third countries, influence the arrival of fewer protection seekers, or

– through so-called return partnerships or also deportation sponsorships – for example by helping Greece to obtain travel documents from the third country to which deportation is to take place, or by ensuring that the country agrees to the return. Only if the person cannot be removed even after eight months does the Member State have to take him or her in.

If the camps are overcrowded, the Commission can insist that member states take in refugees. But even then member states can resort to repatriation partnerships. With this proposal the Commission is going a long way towards accommodating countries like Hungary or Poland, which have boycotted any redistribution up to now - and is accepting that the European asylum system will fail once more. In many cases deportations can't be carried out because the third country in question won't cooperate. The European border protection agency Frontex already has the task of helping member states with deportations. It is completely unclear how return partnerships are supposed to additionally contribute to reducing obstacles to deportation.

The Commission's proposal will not prevent another Moria. The camps at the external borders will remain overcrowded because member states can take in people as they see fit and repatriation partnerships will only lead to more people without the right to stay being sent back in the fewest cases. The losers of the Commission's proposal are the countries at the EU's southern external borders. The profiteers are member states like Germany or Sweden. Because of the tightening of the Dublin rules they can count on being able to shift more of the responsibility for refugees who have moved to their country irregularly to countries like Greece.

The crisis mechanism

In its position on the last Dublin reform in 2018, the European Parliament had called for a fair distribution of asylum seekers from the outset. This is now only found in the Commission's proposal for a crisis mechanism. Once the Commission sets the mechanism in motion, member states will be obliged to take in asylum seekers, recognised refugees and people without the right to stay. Unlike in situations of "high migratory pressure", this also applies to admission directly from border camps.

At the same time, however, border procedures are being drastically extended to all those seeking protection who come from a country with a protection quota of less than 75 percent. Detention in border camps is being prolonged, as is the detention of people without the right to stay. This can lead to people without a prospect of staying being detained at the borders for more than a year. The Commission's proposal also provides for refugees who are manifestly in need of protection to be granted temporary protection status without an asylum assessment. It is unlikely that this proposal will find a political majority in the Council. It's not just countries like Hungary that won't want to accept the Commission deciding when the crisis mechanism is triggered and they are obliged to take people in from the border.

What does the pact mean for Germany?

The Commission's proposal will also lead to more asylum seekers being detained in Germany. Refugees who have bypassed registration at the external border and made their way to Germany will also have to undergo a preliminary examination here - under the same detention-like conditions as at the external borders. The pact proposal also does not rule out the possibility that countries like Germany will drastically expand their special procedures. Germany has already introduced accelerated procedures in "special reception facilities" with the 2016 Asylum Package II. So far, they apply mainly to asylum seekers from safe countries of origin, such as the Balkan countries, and have so far only been carried out at two locations, in Manching/Ingolstadt and Bamberg.

With the pact as proposed by the Commission, the federal government could drastically tighten the conditions in the "special reception facilities" and turn them into closed facilities like those at the external borders. It would have the option of detaining protection seekers who arrive in Germany irregularly from a country with a protection quota of less than 20 percent under the same detention-like conditions as in border procedures.

– So far, asylum seekers in Manching and Bamberg have to live in the camps and are not allowed to leave the district, but they are not locked up.

– The drastic expansion of de facto safe countries of origin to all countries with a protection quota of less than 20 per cent would affect considerably more asylum seekers than before.

– The time limit for fast-track asylum procedures is currently one week and could be extended to 12 weeks under the pact.

The Commission's proposals from 2016 on the accommodation of asylum seekers and on asylum procedures, which are now also to be adopted with the pact, already amount to a significant tightening. The new proposals threaten to further undermine refugee protection.

Rescue at sea will not be strengthened

As part of the pact, the Commission has published two non-binding recommendations on the criminalisation of NGOs and on sea rescue. However, this does not strengthen the rescue of refugees. The Commission recommends that member states should not criminalise sea rescue NGOs for saving human lives. At the same time, however, sea rescue NGOs should be held to a higher standard.

The Commission wants closer cooperation between coastal states and flag states such as Germany, under whose flag NGO ships rescue people in the Mediterranean. They should ensure that safety at sea is increased and that "relevant rules on migration management" are observed, for example against people smuggling. The Commission's recommendation is thus along the same lines as the German government.

It had already increased the security requirements for NGO rescue ships a few months ago, thus taking smaller NGO ships out of circulation. According to the Commission's proposal, refugees rescued from distress at sea will in future be treated in the same way as asylum seekers at land borders: they will have to undergo a preliminary examination under detention-like conditions and remain at the border during the asylum procedure

if they come from a country with a recognition rate of less than 20 per cent.

As long as they are in the border camp, they will not be redistributed to other Member States. The solidarity-based distribution of rescued persons to other member states is supposed to work in a similar way as in the case of high "migration pressure". Member states do not have to take in rescued persons, but can instead also take on deportation partnerships or send border guards.